First Scene of a Play – Grab the Audience from the First Line

When you sit down to write a play, the first scene feels like the front door. If it’s stuck, nobody walks in. A good opening does three things: it sets the world, shows a character in trouble, and hints at the conflict that will drive the story. Keep it tight, keep it clear, and give the audience a reason to stay.

What the Opening Needs

First, decide where the play lives. Is it a dusty kitchen, a bright city street, or a fantasy castle? A short line of description or a piece of set‑up dialogue can paint the picture fast. Second, introduce a character who wants something. Want can be a big goal or a tiny need – a teenager who wants to beat the school bully, or a queen who wants her crown back. Finally, drop a question or a problem that won’t be solved right away. That question pulls the audience forward.

Easy Steps to Write It

Step 1: Write a one‑sentence hook. Think of it as the headline of a news article. Example: “The lights go out, and the only sound is a scream from the attic.” Step 2: Add a character in the middle of that hook. Who is shouting? Who is scared? Step 3: Give that character a clear desire. Maybe they want to find the source of the scream before the power returns. Step 4: End the scene on a beat that leaves the audience hanging – a door slamming, a phone ringing, a line of dialogue that asks, “Did you hear that?”

Practice by writing a 2‑minute scene that follows this pattern. Read it aloud. If you can feel the tension rise, you’ve got the right structure.

Another tip is to use conflict right away. Conflict doesn’t have to be a big battle; a small disagreement works too. Two friends argue about a missing toy, and that argument hints at deeper family drama. The key is that the audience senses something is off and wants to know why.

Don’t overload the opening with backstory. Trust the audience to pick up clues as they go. A line like “I’ve lived here for ten years, but never saw a snowflake in June” tells you about the setting and hints at something strange without a lecture.

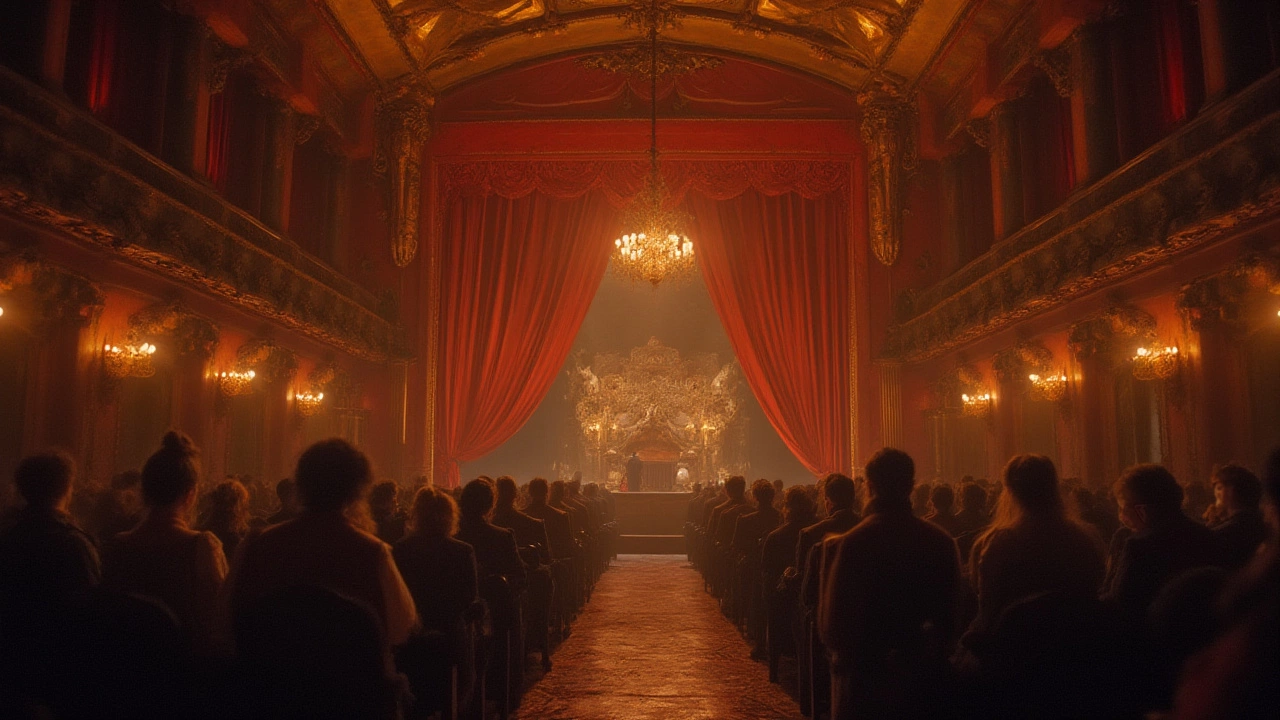

Finally, watch a few stage productions and note how they start. Many classic plays open with a strong image: “A street in London, night. A lone figure leans against a lamppost.” That visual does a lot of work before any words are spoken. You can do the same with a simple stage direction or a sound cue.

Remember, the first scene is your chance to make a promise. If you promise mystery, give a mystery. If you promise laughter, give a joke that lands. Keep the promise front and center, and the rest of the play will have a solid footing.

First Scene of a Play: Name, Meaning, and Fun Facts about Opening Moments in Theatre

Explore what the first scene of a play is called, why it matters, how writers use it to draw you in, and a collection of fun facts and tips about dramatic beginnings.